Oral language skills are crucial for literacy, as well as for overall success and happiness in life. LanguageLift is MultiLit’s new oral language intervention program.

One of the defining features of the human species is that we talk to each other. We talk to our friends, family, colleagues, pets, strangers, ourselves, and to our babies, long before they can talk back to us. We use language – either spoken, signed or written – in everything we do. Oral language difficulties that begin in childhood can have a much wider impact than we might first think.

As language skills are so important for literacy, and overall success and happiness in life, it is crucial to identify and manage oral language difficulties early. Learn more from Speech and Language Specialist Anna Taylor, and Product Developer and MultiLit Research Unit Member Dr Anna Desjardins, below.

Oral language and literacy

Oral language is the most common way that teachers share information with students in a classroom, making oral language crucial for learning in all academic areas. It is also critically important for developing good literacy skills, as children need to draw on their oral language skills in phonology (speech sounds), vocabulary and grammar when learning to read and write.

Indeed, the US National Early Literacy Panel’s 2008 review of research into early literacy officially identifies oral language as a key factor which consistently predicts later literacy achievement.

“Children who start school with a strong oral language foundation have a much easier time developing good word decoding, reading comprehension and writing skills than those with language difficulties,” says Anna Taylor, who adds that the reading problems of children with language difficulties can present in a variety of ways and emerge at different times.

“Some children become stuck very early on when they are learning how to decode (or decipher) written words. Others may seem to get off to a good start with reading but have problems later in making sense of what they read.”

Reading between the lines

Dr Anna Desjardins explains that making sense of written texts often requires us to combine knowledge of language with our background knowledge to read between the lines.

As an example, she points to just one sentence from the picture book Amelia Ellicott’s Garden by Liliana Stafford, about an elderly lady, Amelia, who lives in a large house next to a block of flats. One night, after a storm destroys her garden, all the neighbours in the flat come out to help her, even though she has never talked to them before. At this point in the story, we come to the line: “Amelia Ellicott is so grateful she turns the colour of a beetroot.”

To understand a sentence like this, a child needs to know:

- What ‘grateful’ means

- What a beetroot is

- What ‘turning the colour of a beetroot’ refers to

- Why being helped by people you haven’t been friendly towards might be embarrassing.

This language and world knowledge must then be applied in context to fully comprehend the text.

“This task is complex enough as it is,” says Dr Anna Desjardins. “For a child with oral language difficulties, who additionally may not have fully understood prior events in the story, it is hugely challenging.”

Assessing oral language abilities

“The key to minimising the consequences of language and related literacy difficulties is to identify children at risk and intervene as early as possible,” says Anna Taylor.

Assessing oral language and identifying difficulties can be a complex process, with language development influenced by many factors, such as language background, genes and social circumstances.

Teachers may notice difficulties with oral language in the classroom, and their concern alone can be an indicator that something is not quite right. However, sometimes behavioural or learning difficulties can hide issues with oral language, or children may be very good at masking their difficulties by following peers or non-verbal cues. This means some children with oral language difficulties can be easily missed.

“As language develops naturally over the first five years of life, children should be entering school with a certain level of oral language competency,” says Dr Anna Desjardins. “Schools are ideally placed to use a quick teacher-administered screening test of oral language for all children on school entry.”

While no single test can accurately capture a child’s language capabilities, a non-diagnostic screening test can help to objectively identify children who might have difficulties. Children identified at risk by screening tests should be followed up with a more comprehensive assessment of their oral language skills – for those with significant difficulties, a speech pathologist should be involved in their assessment.

Some children may benefit from a small-group oral language intervention delivered in school to give them the boost they need to catch up with their peers.

How LanguageLift can help

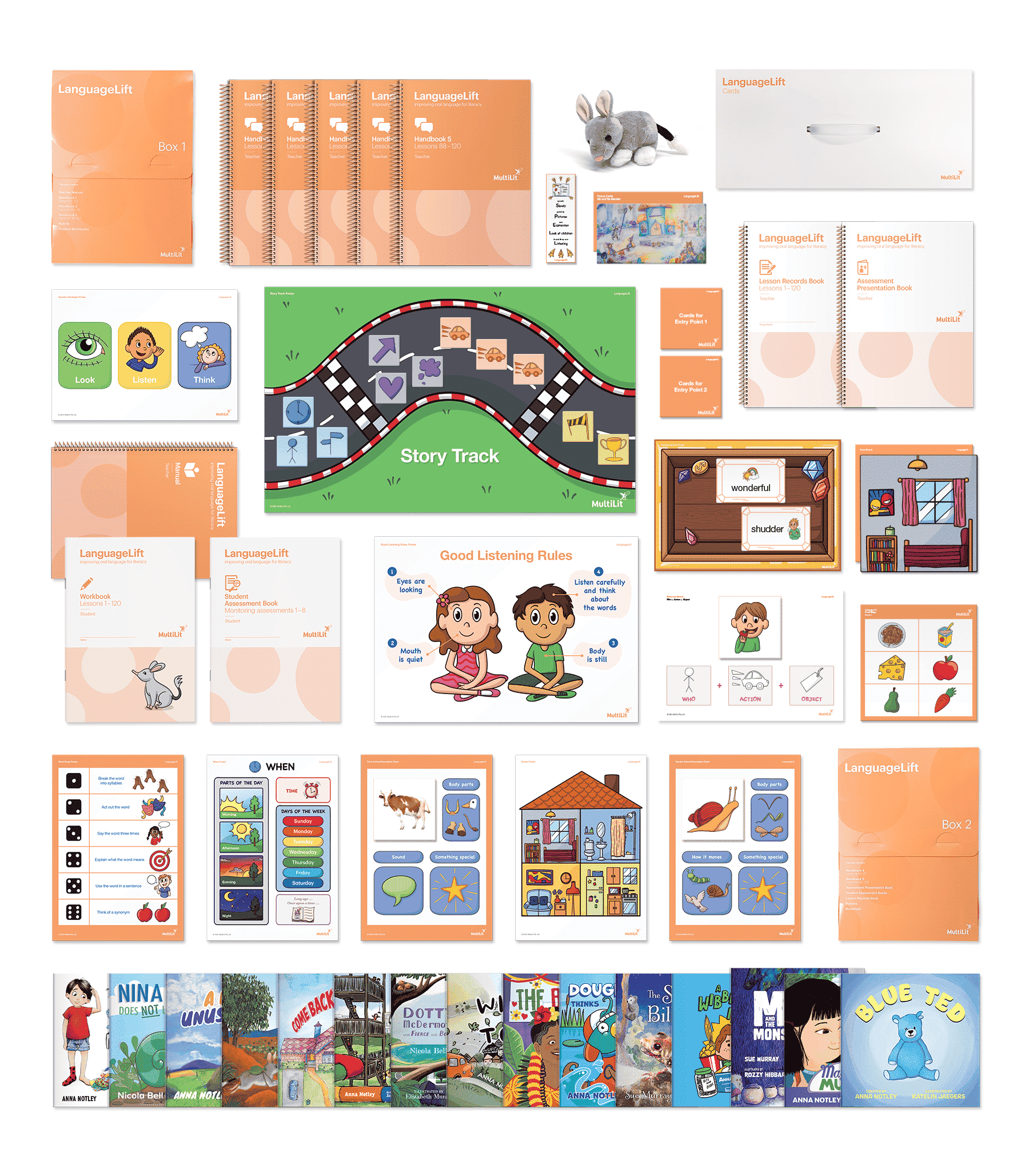

New from MultiLit, LanguageLift is a small-group oral language intervention program designed to improve important skills needed for successful reading comprehension. Skills include:

- Vocabulary – the words children understand and use

- Grammar – rules about how we use and combine words

- Narrative skills – understanding and telling stories.

Recent large-scale studies demonstrate the importance of these core skills for developing reading comprehension and writing abilities, contributing to the best-practice speech pathology and educational research evidence that underpins this new program.

“LanguageLift trials across five schools show children making significantly larger than expected gains in their oral vocabulary, grammar, and story retell and comprehension skills,” says Anna Taylor. “As well as significant positive changes in their social, behavioural and emotional skills.”

“These are exciting results,” says Dr Anna Desjardins. “They show that LanguageLift can provide children with oral language difficulties with the small-group support and rich, scaffolded oral language environment they need to foster language growth.

“We hope, in turn, that this will have more far-reaching effects, contributing to improvements in their reading comprehension (and writing), and generally setting them on a path to a more fulfilling and happy life.”

What else can teachers do?

Dr Anna Desjardins believes that all children, whether they have oral language difficulties or not, benefit when teachers are aware of their role in providing a rich oral language environment in the classroom. Teachers can contribute enormously to the language growth and ongoing literacy success of all children who pass through their classroom by:

- Intentionally using interesting language in discussions across curriculum areas

- Providing explanations about word meanings

- Using storybooks as springboards to explore words and concepts

- Noticing and praising the way children express their own ideas.

“Many children are at risk,” says Anna Taylor. “Schools can help by providing early oral language intervention programs and by referring children who need specialist support to speech pathologists.”

In the classroom, teachers can support children with language difficulties by:

- Supplementing verbal information with visual prompts

- Using simple words and sentences when teaching new and complex concepts

- Breaking tasks down into a series of small steps.

LanguageLift provides teachers with 120 structured, scripted lessons built around 15 purpose-written storybooks, published by MultiLit’s own Putto Press. The lessons and resources of the program are an easy way to implement some of the ideas above to support children with language difficulties and set them on a path to success.